Innovation is a behavioural challenge before it is a technical one

Innovation features in almost every leadership conversation I’m part of today. Over the past two decades, I’ve worked with senior leaders across the United States, the UK, China, Taiwan and now India in organisations that are ambitious, well-resourced, and committed to innovation.

And yet, a familiar frustration keeps surfacing.

Despite strong strategy, investment in technology, and access to world-class expertise, innovation efforts often stall. Leaders are left wondering why breakthrough ideas struggle to translate into sustained impact even when they appear to be doing everything “right”.

The conversation usually turns to process, funding, skills or systems. But in my experience, those are rarely the root cause.

At its core, sustained innovation is a behavioural challenge.

Innovation lives or dies in how people think, interact, challenge, decide and adapt; particularly under pressure and when uncertainty increases. When innovation falters, it is rarely because people lack intelligence or ideas. It is because the behaviours required to navigate complexity become constrained by an ineffective culture, leadership habits, and unexamined assumptions about what “effective” looks like.

Why innovation fails in organisations

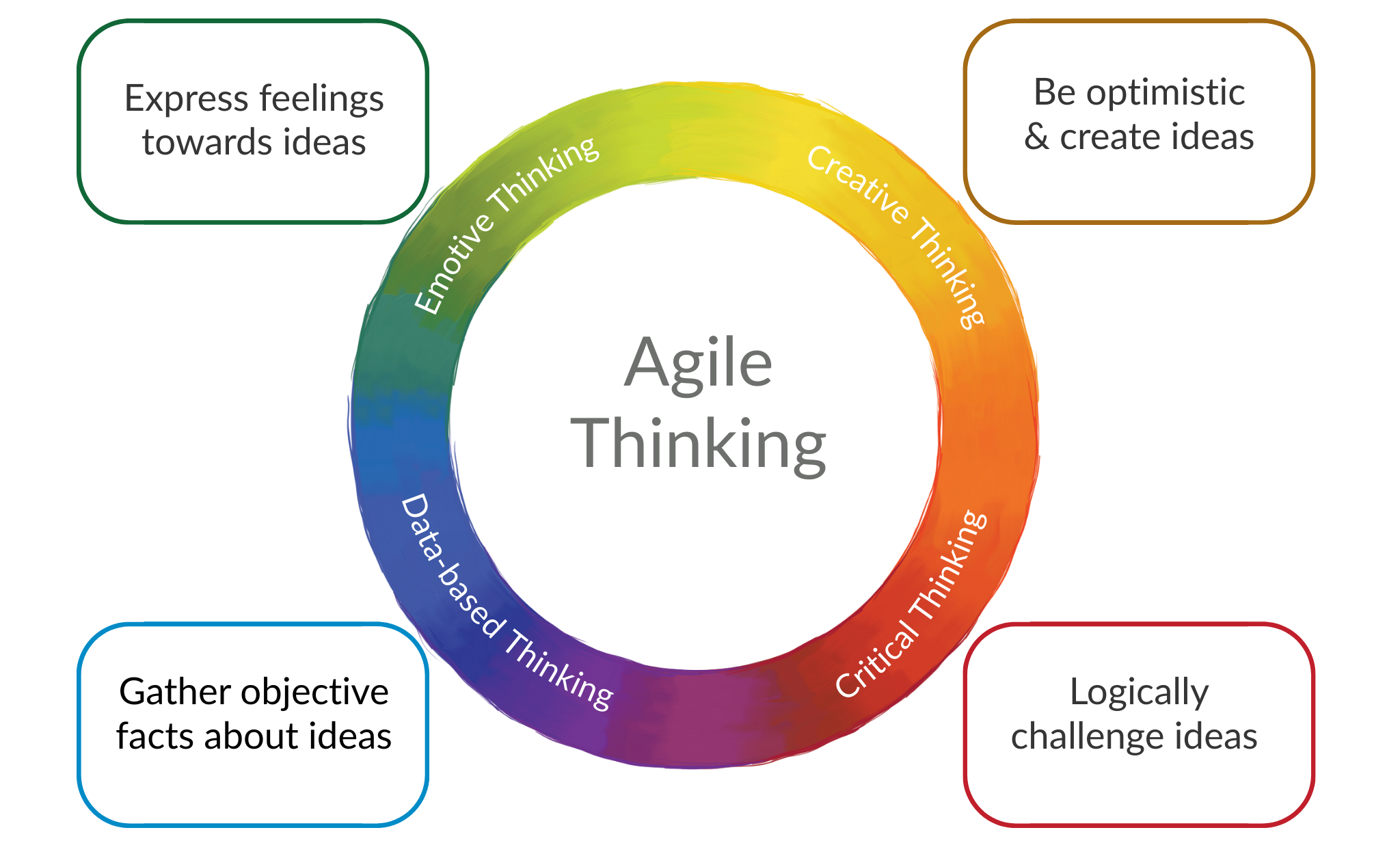

Innovation is problem solving under uncertainty. Whether developing new products, improving services, or rethinking operating models, people are required to interpret information, generate possibilities, challenge assumptions, and adapt behaviour as context changes.

Yet globally between 40% and 90% of innovation projects fail, depending on scope and context. Failure is part of innovation. But most organisations don’t fail because of a loss of intelligence or creativity, but from a narrowing of behavioural agility.

I’ve repeatedly seen organisations fail because:

- Leaders over-rely on behaviours and thinking that once worked, while other perspectives quietly fall away

- Teams mistake different thinking styles for resistance rather than contribution

- Cultures reward consistency when adaptability is needed

As certainty disappears, analysis and logic take precedence over exploration. Risk management overshadows curiosity. Emotional signals from customers, teams and markets are deprioritised in favour of what feels measurable and safe.

Even the most well-designed innovation strategies struggle to translate into success without an accurate, practical understanding of how behaviour can overextend into one way of being.

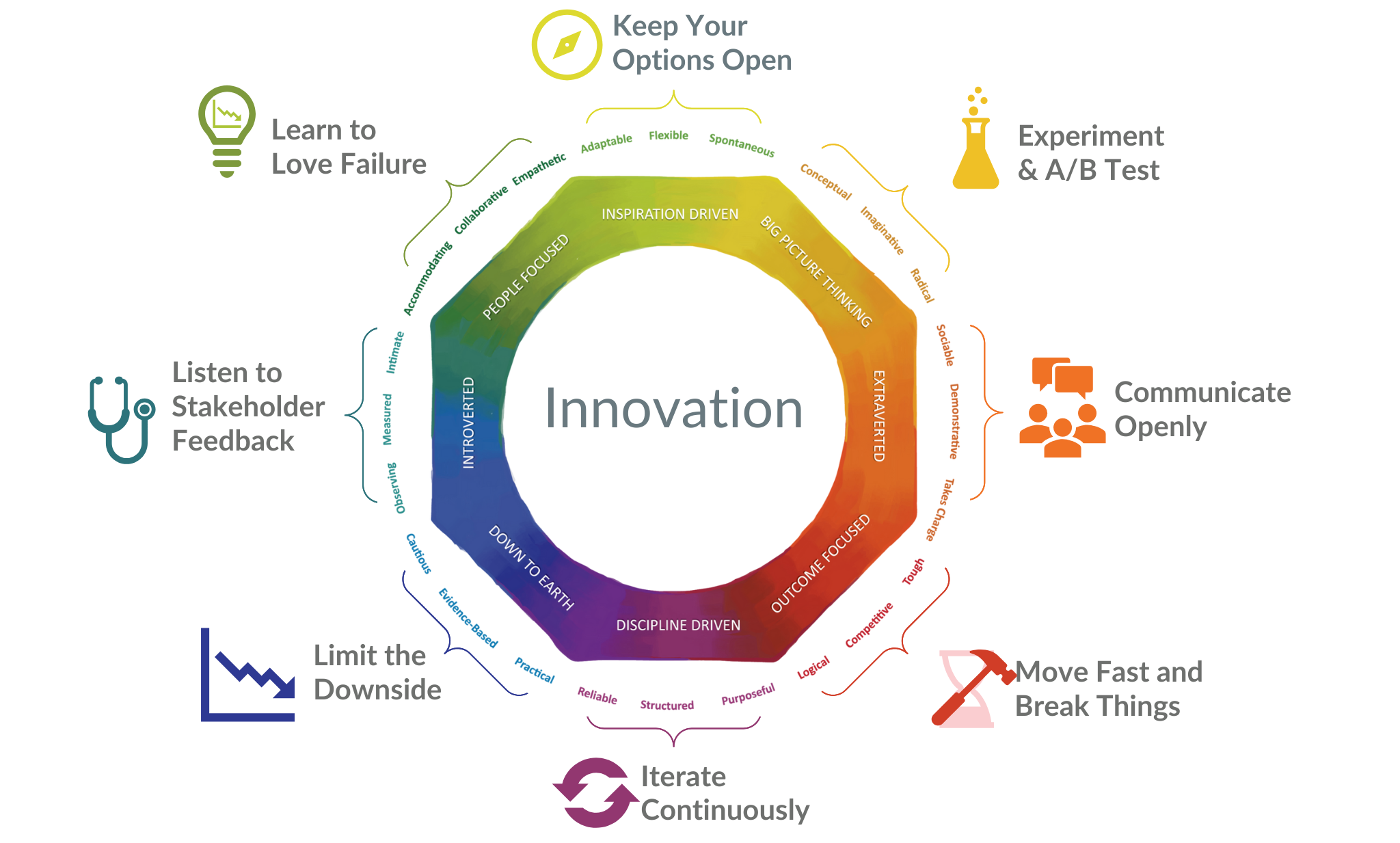

None of this is intentional. Research from Lumina Learning shows that personality can account for up to 18% of the variance in job performance. That is not marginal. It’s a meaningful contribution, and yet behaviour remains one of the least deliberately designed elements of many innovation strategies.

What BlackBerry and Apple reveal about innovation behaviour

The contrast between BlackBerry and Apple illustrates this clearly.

When BlackBerry introduced mobile devices with physical keyboards in the early 2000s, it redefined business communication, capturing around 50% of the U.S. smartphone market. Its early success was built on strengths that mattered at the time: reliability, practicality and a measured approach.

As touchscreen platforms and app ecosystems emerged, those same strengths became increasingly over-relied on:

- Cautious, evidence-driven perspectives were rewarded

- Risk mitigation became narrow-sighted

- Bolder ideas were questioned early, often framed as unrealistic or risky and ultimately abandoned

As competitive pressure increased, BlackBerry narrowed its behavioural agility instead of expanding it.

Many organisations fail not because they stop innovating, but like Blackberry, they overextend into one area of their strengths and struggle to adapt their behaviour as markets and expectations evolve.

Apple on the other hand faced the same uncertainty but illustrated what sustained innovation looks like on a human level. Rather than over relying on a single way of being, Apple was willing to let go of what already worked and created space for different perspectives to coexist:

- Exploration sat alongside discipline

- Challenge was balanced with empathy

- Intuition and emotional insight about how people would experience technology were held in tension with evidence and engineering rigour

The difference was not technical capability or resource. It was the behavioural adaptability to move deliberately between exploration and scrutiny, intuition and evidence, imagination and discipline precisely as the situation demanded.

3 behavioural factors behind sustainable innovation

Across decades of working with leaders and teams, I’ve consistently seen innovation accelerate when organisations take a more precise and human-centred view of behaviour.

For leaders serious about developing and adapting more effective behaviours to support innovation, here are three core principles from Lumina Learning’s evidence-based yet humanistic approach that I’ve seen countless organisations globally succeed with:

1. Innovation snakes and ladders: The power of The Three Personas

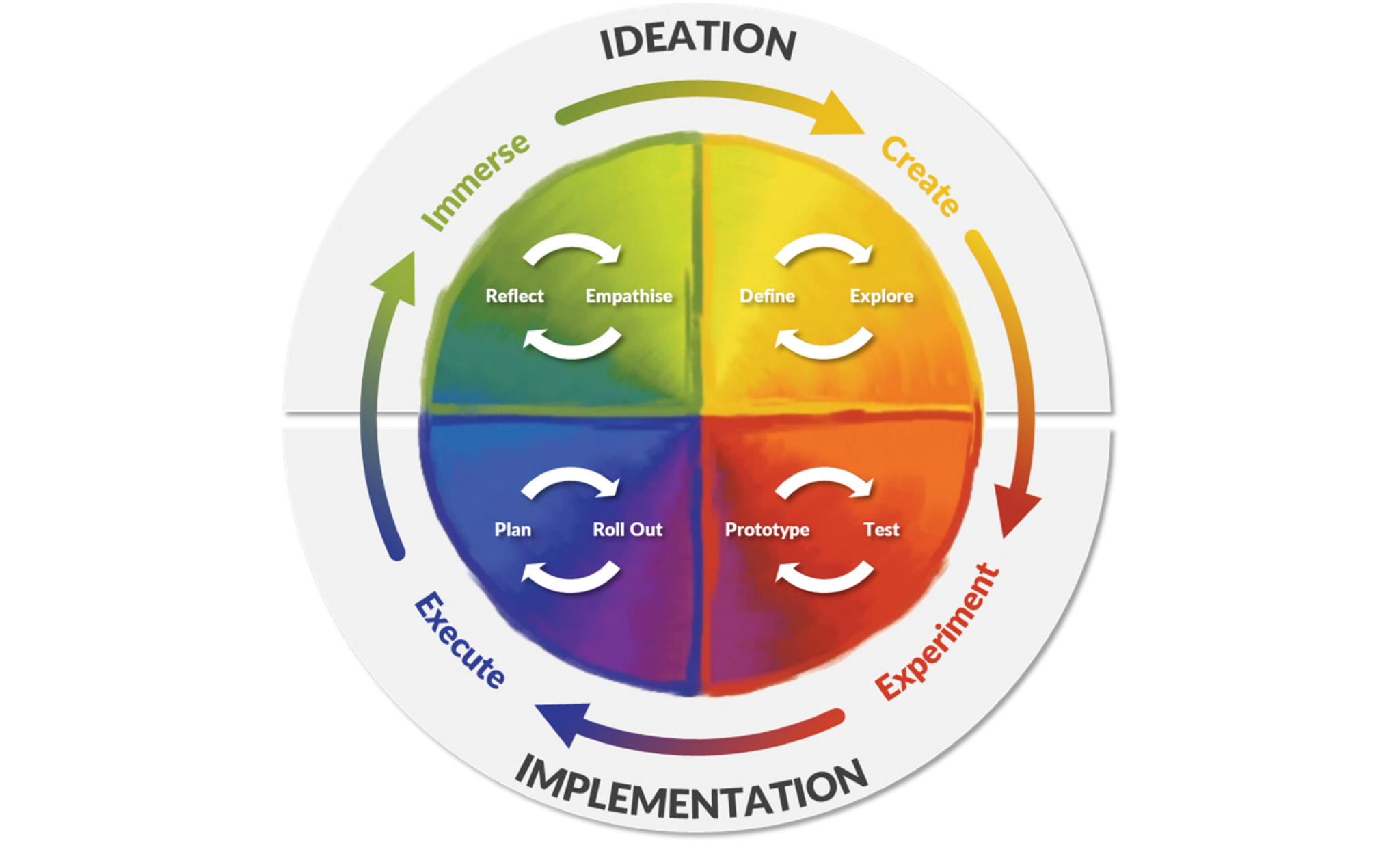

One of the most impactful insights for senior teams is recognising that behaviour changes under different conditions.

In the Lumina Spark framework, these shifts are captured through three behavioural personas, providing a practical lens to understand how the same strengths can either help teams move towards innovation or quietly pull them off course:

- Underlying Persona – People’s natural strengths and hidden potential

- Everyday Persona – How people typically adapt their behaviour to operate at work

- Overextended Persona – How those same behaviours may become ineffective under sustained pressure

I like to think of how The Three Personas support innovation as a game of snakes and ladders.

When teams feel valued, engaged and energised, they bring a rich mix of different thinking and strengths from their Underlying and Everyday Personas. They question assumptions, imagine alternatives, test ideas rigorously and sense impact beyond data. These behaviours act as ladders, helping teams move innovation forward.

But innovation rarely happens in comfortable conditions.

Under scrutiny, ambiguity and time pressure, behaviour can overextend. The same strengths that once helped teams progress can quietly turn into snakes, blocking their momentum when over-relied on.

For leaders driving transformation, this matters deeply. When leaders recognise which behaviours are acting as ladders and which have become snakes, they stop personalising behaviour and start to design roles, workloads, and team interactions more intelligently.

When these shifts are recognised, adapted, and acted on more effectively, organisations can build the behavioural capability required not just for effective leadership and teamwork, but for sustained, scalable innovation.

2. Where innovation succeeds: Embracing the Paradox

Innovation often feels difficult because it requires leaders and teams to hold opposing strengths at the same time.

Effective innovation requires:

- Imaginative vision and evidence-based thinking

- Flexibility for inspiration and a structured approach

- Taking charge to move forward and stepping back to observe

- Empathy and challenge

Innovation does not live at either extreme. It lives in the tension between them. Too often, organisations instinctively resolve these tensions too quickly, treating them as clashes rather than complementary strengths.

Teams that sustain innovation do the opposite. They allow opposing perspectives to coexist long enough to inform better decisions. They resist shutting down disagreement prematurely. They recognise that discomfort is often a signal that something new is emerging.

This reframing is powerful. It shifts the conversations from “who is right” to “what is required now” and enables teams to stay adaptive when certainty is low and the stakes are high.

3. The performance payoff: Valuing different ways of being

In any innovation effort, teams need people who generate possibilities, people who test assumptions, people who ground decisions in evidence, and people who tune into human impact and emotional response.

When organisations intentionally value different ways of being, the performance impact becomes tangible. Three things tend to improve quickly:

- Speed to clarity: Fewer circular conversations, clearer framing of the real problem, and less time spent revisiting decisions later

- Quality of decisions: More perspectives are tested before commitment, reducing blind spots and increasing confidence in the chosen direction

- Execution energy: Less silent resistance and greater shared ownership, because people can see their perspective reflected in the outcome

It’s not just about who is in the room, but how people show up together. Research consistently shows that the value of cognitive and behavioural diversity is realised most fully when teams actively share knowledge, manage tension constructively, and build psychological safety. Behaviour remains the multiplier, not the mere presence of difference.

Valuing different ways of being does not mean encouraging everyone to contribute in the same way. It means designing conversations and decisions so different perspectives are deliberately invited, sequenced and integrated, rather than smoothed over in the name of alignment.

When this happens, behavioural agility expands. And with it, the ability to innovate effectively.

Innovation is human-centred before it is technological

As technology continues to accelerate idea generation, analysis and execution, the real differentiator will not be access to tools.

It will be how effectively leaders design the behavioural conditions for innovation to thrive.

Even the most advanced systems cannot compensate for cultures where behaviour narrows under pressure, difference is silenced, or tension is avoided. Conversely, organisations that understand how people think, interact and adapt when certainty disappears are far better positioned to scale innovation, manage risk and convert ideas into sustained performance.

Innovation does not start with systems, processes or platforms.

It starts with behaviour: how people challenge assumptions, work with difference, and make decisions together when the answers are not yet clear.

That is the real work of innovation.

And it is, at its core, profoundly human.

I’ll be further expanding on the link between these three behavioural drivers and innovation at an upcoming Lumina Learning Conference in India, taking place across Mumbai, Bangalore, and Delhi from late February to early March.

If you’re interested in how personality psychology continues to shape how organisations think about behaviour, innovation and performance, do come along and join the conversation.

Let’s explore

- How personality sparks innovation that AI cannot replace

- Where AI can enhance innovation and where it can quietly constrain it

- How leaders can intentionally combine human insight with intelligent use of AI to create real organisational impact

Dr Stewart Desson

Founder & CEO, Lumina Learning

Business Psychologist, Creator of the Lumina Spark psychometric.

Stewart is a leading expert in psychometrics and organisational development. Through Lumina Spark, he developed an innovative way to reduce the bias often found in traditional personality models by combining rigorous data with a humanistic approach. His work focuses on helping organisations grow through improved self-awareness, communication, leadership, and team effectiveness.

Curious how Lumina Learning could help your organisation?

Contact us below to learn more